Does a Fed Rate Increase Doom Housing?

by Mark Fleming, chief economist, First American. Article originally published in the 2015 October Edition of REAL Trends.

While the Federal Reserve hasn’t raised rates yet, it could potentially decide, before the end of the year, to increase interest rates for the first time since 2008. The CME FedWatch Tool measures the market’s expectation of Fed target rates. One argument is that rising interest rates cause affordability to decline, which is true. Many contend that declining affordability leads to a reduction in demand, which is not necessarily true and that a reduction in demand means house prices will fall, which is not necessarily true either. People may adjust how much housing they demand, rather than drop out of the market altogether. Of course, marginal borrowers may truly be priced out of the market, but it’s not clear that this reduction in demand would be significant enough to trigger falling prices. A slowdown in the pace of price appreciation is a much more likely outcome.

I have argued here, as others have, that rising rates don’t necessarily cause a negative demand shock and falling home prices. When the Fed raises interest rates, it’s because the Fed believes that the economy is strong enough to adjust and has the potential to begin overheating (that’s what inflation measures). A stronger economy, more or better jobs, rising wages, increased confidence – these factors all increase demand for housing. In other words, rising rates are indicative of increased home sales and upward pressure on prices.

So, what scenario plays out if the Fed raises rates? Does reduced affordability win, or the better economy? Alas, we only observe the net effect of the two, but using our proprietary model of U.S. housing market existing-home sales demand and house prices, we can “ask” exactly what the net effect might be. In this case, what happens to existing-home sales and house prices when the Fed increases interest rates later this week by 0.25 percent, and that causes a permanent upward shift in mortgage rates by the same amount?

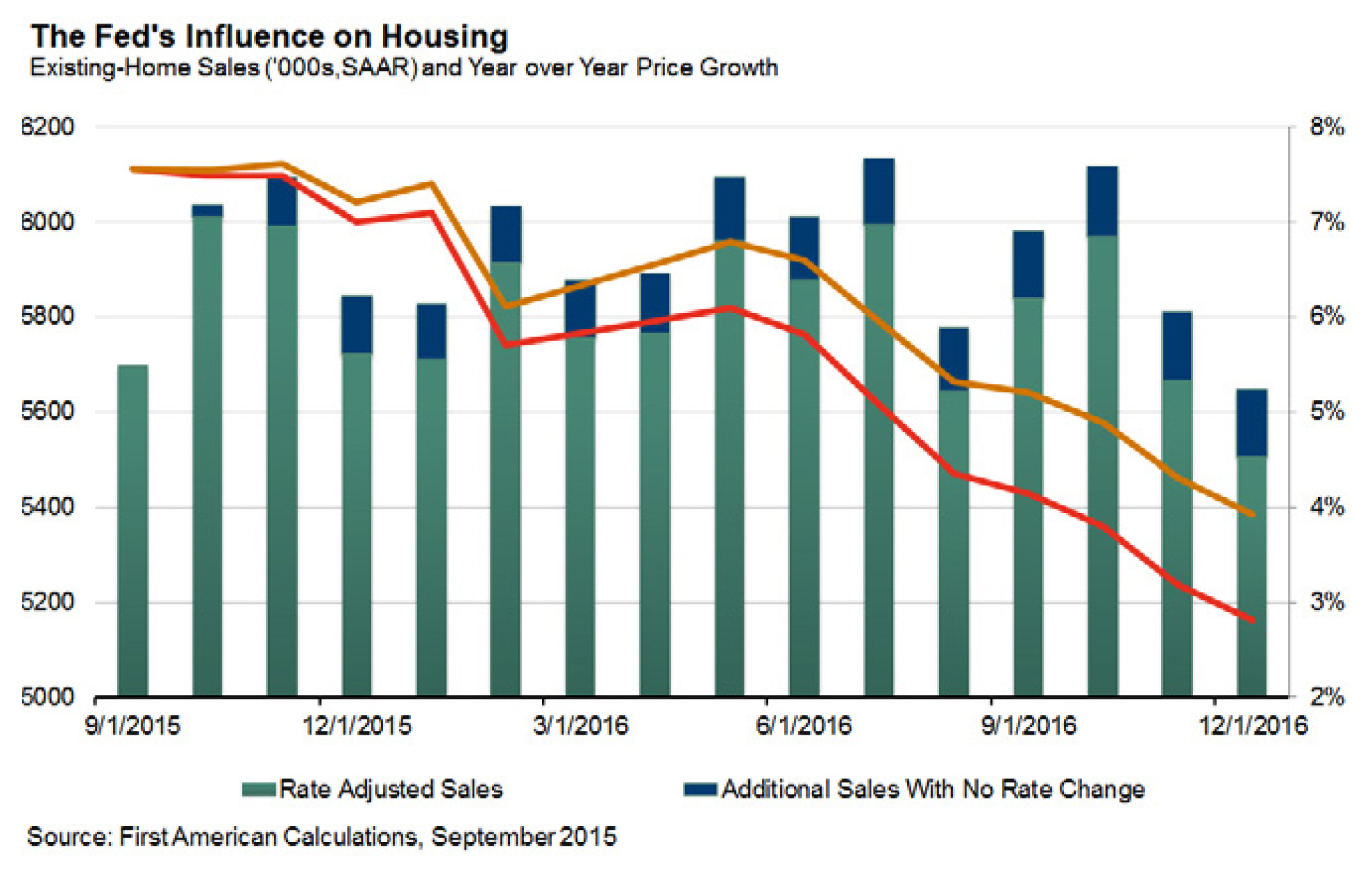

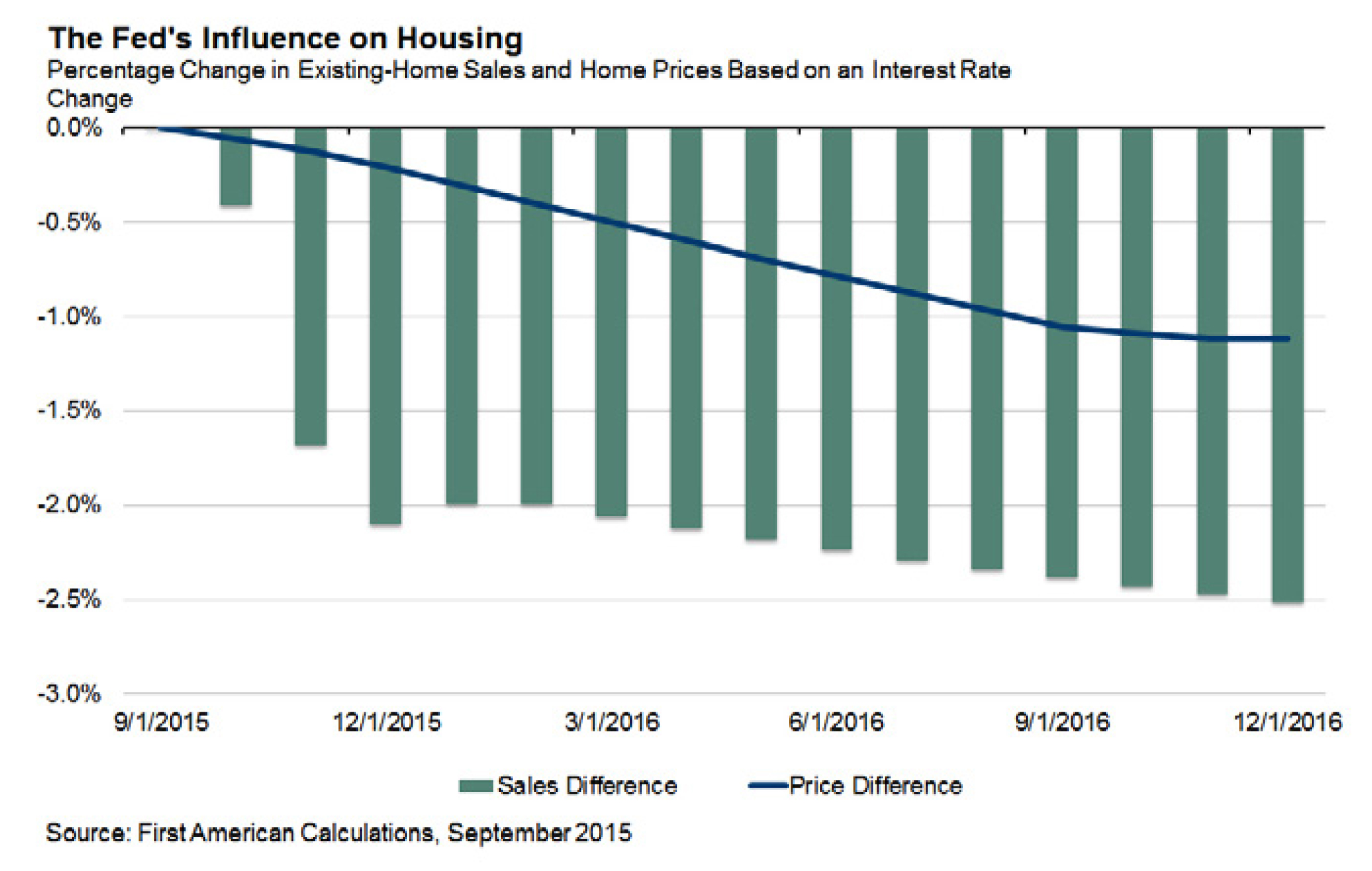

In the two figures below, we show the hypothetical result of a 0.25 percent increase in the 30-year fixed rate mortgage rate this month caused by a Fed rate increase this week, and how that may influence the amount of existing-home sales demand and house prices through the end of 2016. The first figure shows home sales and price changes, both with and without the rate increase. The second figure shows explicitly the differences between the two scenarios.

House price appreciation, on a year-over-year basis, does slow down, but only by 1 percent more than it is expected to slow down anyway. Existing-home sales also slow down, by about 2.5 percent on annualized and seasonally adjusted basis by the end of the time horizon. That turns out to be a hypothetical decline of fewer than 150,000 sales a year.

Of course, we cannot be sure exactly how mortgage rates and the housing market will respond to a Fed rate increase. But, we can say with some certainty that the Fed will eventually raise rates. When it does, the housing market isn’t doomed to fail, but rather adjust to the reality of interest rates that are reflective of a strengthening economy and certainly more traditional financial conditions. Is the housing market doomed? No, but the housing market will modestly adjust to a Fed rate increase.

COMMENT FROM REAL TRENDS

“Manfredi lays out carefully thought-through considerations about the impact of a rate rise by the Fed on housing sales and prices. It all makes perfect sense. But, in the last 40 years, I have noted that once the Fed begins to raise rates, the reaction of the housing market is for buyers who may have been on the sidelines to jump in before rates rise further. A small rise will provide some impetus for those wanting to get in become more motivated to do so.

“Another factor to consider is that the REAL Trends Housing Market Report is already signaling a slowdown as the year-over-year increases in unit sales and average price increases are already slowing.

“Lastly, when we consider the benchmark of 4.5 percent of all households typically buying each year. We are right on that line now, so that would indicate that we are already at the cyclical peak of housing sales given the level of households and household formations. A flat to slow growth housing markets is already almost a sure thing.”